Research Brief 25

Among the lighter sentences awarded to those convicted in the Victorian Supreme Court in the nineteenth century was that of ten days imprisonment handed down to James ‘Charley’ Davidson in March 1865. His offence, however, was more weighty, its context more global than local in significance.

The pages of the Supreme Court register record that Charley was committed for trial at Williamstown, the portside town not far from Melbourne, on 16 February 1865. There he had been charged by police with ‘enlisting into a foreign service’, after being earlier arrested disembarking from a boat leaving from the SS Shenandoah, a vessel then tied up at Williamstown. Charley was one of four men so arrested: one managed to escape further prosecution as he was not a British subject; another was acquitted at trial as he was a youth; only William McKenzie shared Charley’s fate, both of them receiving their light sentences at the hands of Justice Molesworth after being found guilty, in the words of the court-book, of ‘attempting to enter in service of [a] foreign power’.

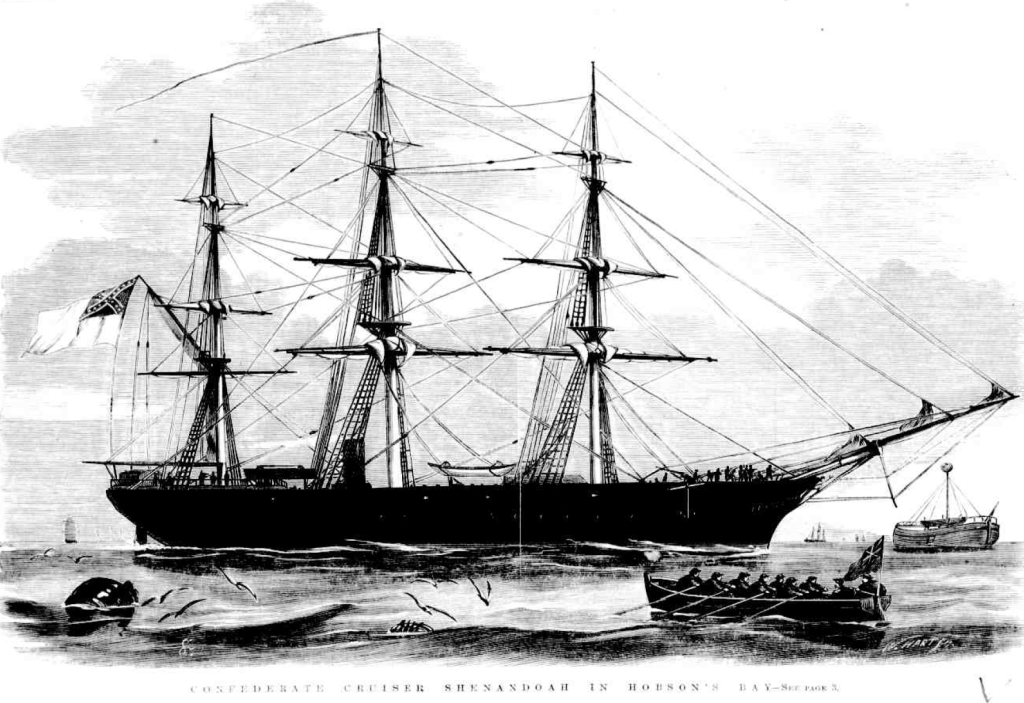

This was no ordinary prosecution. It had been directed by the Victorian Executive Council (the governor in council with his ministerial advisers) as one of a number of measures in their confused response to the arrival and prolonged stay of the Shenandoah from late January. As its name signalled, this was a vessel with American affiliation, in the service of the rebellious Confederate States that had been at war with the Federal Government of the United States since 1861. By the time of the ship’s arrival the Civil War was drawing to a close – but at a time before cable, communication about the state of the war was only as fast as the shipping mail. It was known though that this was no merchant vessel, but one engaged in the bloody business of attacking and destroying the merchant shipping of the United States.

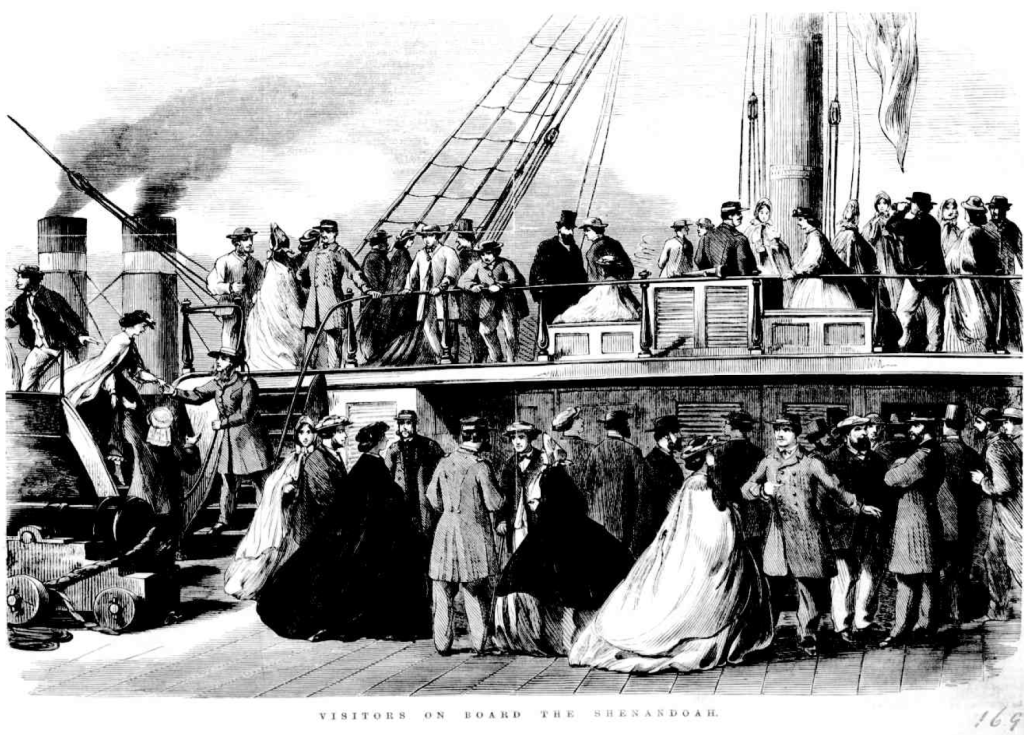

The arrival of the Shenandoah divided Melbourne. For some, especially the US consul in Melbourne, William Blanchard, the vessel was nothing better than a pirate ship and so should be seized by the government. For others, it was a vessel of a belligerent power and so should be subject to the international law governing such – that it leave the port as early as possible but in any case not within 24 hours of a vessel belonging to the other combatant power, in this case the United States. There was no shortage of defenders of the Confederate cause in Melbourne, some of them Americans who had flooded in with the gold rushes. And a fair section of ‘British’ colonial opinion regarded the Confederate states as engaged in a rightful claim of self-government, the kind that Victorians wanted for themselves.

The colonial response was overlain by the policy of the imperial government. After the outbreak of the war in 1861, Queen Victoria had issued a proclamation of the British Empire’s neutrality. While this limited the help that might be given to either side it also entailed a recognition of the belligerent status of the Confederacy, and so was an impediment to the Victorian government acting against the Shenandoah as though it was a pirate ship.

Over a number of weeks, the governor and the Executive Council proved themselves out of depth in dealing with the challenge of enforcing neutrality. Nevertheless, it repeatedly warned the captain against any attempt to recruit sailors for service on his vessel. So when police were alerted to the presence on the ship of a number of men who were suspected of enlisting, they moved on Charley and his three companions who had been seen at night in a boat near the Shenandoah.

James was a 22-year-old sailor from Scotland, not long in Victoria. He was a British subject and so amenable to the jurisdiction of the Victorian courts. Against him in court were a number of witnesses, marshalled by the very active US Consul. Some had been encouraged to abandon the ship. Much fun was made by Charley’s counsel, the leading Melbourne advocate, Butler Cole Aspinall, of the fact that a principal witness was a ship’s cook, John Williams. Williams had been taken from one of the ships that the Shenandoah had seized and sunk in November 1864. His identity as an African American may have added venom to Aspinall’s attempt to ridicule the prosecution.

Justice Molesworth was not brow-beaten by Aspinall, even if the light sentence indicates equivocation over Charley’s culpability. The facts were that Victoria was bound by imperial neutrality, which had been proclaimed by the Queen and published locally in 1861 – and so an attempt to recruit labour for a war vessel was illegal, a breach of the provisions in the Foreign Enlistment Act of 1819. Not able to implicate Captain Waddell, who did no more than deny that he was engaged in the business of gathering men for service on his war-ship, the Victorian government targeted those who might be enlisting.

Charley’s conviction was nothing compared to the damage being done to the imperial government by colonial Victoria’s prevarication over the Shenandoah. After leaving Melbourne the vessel sailed into the North Pacific and for a number of months attacked the US whaling fleet, destroying a large number of ships and seizing their cargo. Without the coal taken on board at Melbourne, and the labour recruited, the Shenandoah could not have sustained its pillaging. So after the United States in 1871 sued the United Kingdom for its heavy losses at the hands of Confederate shipping, the Shenandoah’s Melbourne stopover was ruled by an international court of arbitration in 1872 as an element of the liability.

Charley got ten days, but Captain Waddell’s stay in Melbourne cost the British government more than £800,000.

(For more on the case of Charley, and the Shenandoah, including newspaper accounts, search for James Davidson 1865 on our public search site at https://guprosproprod0.wpengine.com. And for longer histories see Cyril Pearl, Rebel Down Under, 1970; Terry Smyth, Australian Confederates, 2013; Ernest Scott, ‘The ‘Shenandoah’ Incident’, Victorian Historical Magazine, vol. 11, no. 42, 1926 (available online at State Library of Victoria website).

Author: Professor Mark Finnane

To cite this research brief: Mark Finnane, ‘A foreign fighter’, The Prosecution Project, Research Brief 25, https://prosecutionproject.griffith.edu.au/a-foreign-fighter (1 November 2016, viewed 2 November 2016).