Andy Kaladelfos examines the historical ability of the criminal justice system to respond to sexual abuse within the family.

Research Brief 26 – originally published as part of the Australian Women’s History Network’s 16 Days of Activism Against Gender Violence series.

The sexual abuse of children is overwhelmingly perpetrated by people known to victims. National data collected by the Australian Bureau of Statistics ‘Personal Safety Survey’ in 2005 found that victims knew eighty-nine per cent of perpetrators of sexual abuse. Amongst the highest categories, respondents indicated that family members were responsible for forty-five per cent of abuse, with at least fourteen per cent involving fathers and step-fathers.

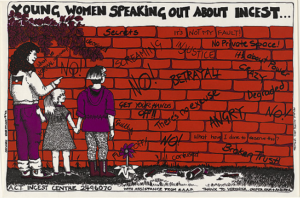

Familial sexual assault and incest are often described as an ‘unspeakable’ offences: occurring in the private sphere and hidden from public view. Making sexual abuse in families visible was an important part of feminist activism and scholarly inquiries of the 1970s and 1980s.

YOUNG WOMEN SPEAKING OUT ABOUT INCEST, KATH MCCANN, 1992. GIFT OF MEGALO ACCESS ARTS INC 1993, IMAGE VIA NATIONAL GALLERY OF AUSTRALIA COLLECTION.

In the 1980s, Linda Gordon’s pioneering analysis of the records of Boston’s child protection agencies showed that sexual abuse in families was an offence well-known to authorities: at least ten per cent of records contained references to familial child sexual abuse. Gordon explains that in the late nineteenth century child protection advocates were ‘aware of it and taking action against it’. But this changed in the first half of the twentieth century when they came to blame the crime on child ‘sex delinquency’. Concern about sexual abuse turned outward, towards stranger abuse rather than abuse perpetrated in the home until the feminist interventions of the 1970s.Alongside their colleagues in law, criminology and elsewhere, feminist historians wanted to uncover the treatment of incest and its relationship to patriarchal systems of power. Of course, historians do not have access to self-reported data like the Personal Safety Survey in order to estimate the extent of incest or the state’s responses to it. So those studying the problem looked to other data sources to reconstruct this history.

Australian child protection workers in the late nineteenth century seem to have had far less interest in recording or acting on sexual abuse in the family than those in Boston. Dorothy Scott and Shurlee Swain’s authoritative history of Australian child protection found that sexual abuse was mentioned in as little as two to a maximum of five per cent of the records of agencies, with child neglect and cruelty dominating their agendas.

In the realm of criminal justice, however, Australia was amongst the first in the British world to make legislative attempts to tackle the problem of familial child sexual abuse. Sexual offences within families had previously been prosecuted under general sexual offence provisions in the criminal law, but in the late nineteenth century legislators created specific offences. South Australia in 1876, followed by Queensland and Western Australian in the 1890s, were the first states to create the criminal offence of ‘incest’. Other states created what we might call ‘relational’ offences: offences that were deemed more serious by the power relationship of offender to victim, thus sexual offences by fathers, and later step-fathers, were subject to a higher age of consent and higher maximum penalties than other sexual offences.

Assessing the deployment of the criminal law against familial sexual offences is difficult because of the nature of the historical data and prosecution practices. If we just look at those charged with specific relational offences, we will underestimate the number of family child sexual abuse cases that appeared before the courts. Although these relational offences existed, police and prosecutors often charged fathers with general child sexual assault provisions and if the offence was an indecent assault (i.e. a non-penetrative offence), there was no differentiation of familial offences from others. In Queensland, for example, the use of ‘incest’ provisions accounted for only six per cent of indictable sexual offences, while sexual offences examined at the case file level in New South Wales suggest up to twenty-five per cent of indictable offences against girls under the age of consent involved family members. Once these cases appeared in the higher courts they had a strong chance of a successful prosecution: in Queensland sixty-seven per cent and in New South Wales seventy-five per cent of cases resulted in convictions.

Certainly the law contained provisions for prosecuting offences within families, but a major impediment lay earlier in the criminal justice process. The reporting of abuse in Australia was very unlike that of New York City one hundred years ago where child protection workers were actively involved in the investigation of sexual abuse. In Australia, police investigations of abuse relied on families, particularly mothers, to make complaints.

Reliance on individual reporting was a particular problem in policing familial sexual violence due to family’s reluctance to report the offence. In the study that Lisa Featherstone and I conducted on the prosecution of sexual offences in the 1950s we found that the chief reason for family’s reluctance to report abuse was a very real fear of poverty.

In the 1950s, it was difficult to survive without a male breadwinner, and few lone mothers could support themselves and their children. Without an adequate welfare system, mothers were aware that their families would not remain intact if they reported abuse. In court records, mothers and other family members describe weighing up their own experiences of physical or sexual assault and the abuse of their daughters with the destitution that would be brought to bear on their families if their husbands were incarcerated.

In the place of reporting, some mothers developed means of ad hoc surveillance of their male partners, whereby they attempted to monitor men’s sexual behaviour around their children without notifying police of their husband’s criminal activities. Alongside these pressures, dynamics of control in families meant that accused men often blamed their wives for their assault of their children. For example, one defendant who had assaulted his daughter when his wife in hospital told police he ‘had no control over himself’ while his wife was away. Some fathers even explicitly described their daughters as a sexual substitute for while their wives were absent from the family home.

The financial pressures, social shame and the threats of violence brought on mothers in familial child sexual abuse cases meant that offences often came to light at moments of crisis – when the abuse was revealed to those outside the family; when mothers’ surveillance of their own homes failed; when pregnancies of their daughters occurred.

Historically, pressures on family life inhibited reporting of offences as their social consequences reached well beyond the conviction of the defendant and meant that families could be subjected to poverty. Disturbingly, the economic position of families remains an impediment to the criminal prosecution of familial sexual abuse even today. As child sexual abuse expertsJane Goodman-Delahunty and Kate O’Brienexplain, ‘In most cases, the offender is employed and is the main family breadwinner; thus, victims and non-offending parents often face financial hardship by pursuing legal action’.

The blunt tool of criminal law was neither incentive for reporting nor effective in dealing with the consequences for families after state intervention. In some ways, the criminal law punished the family just as much as the defendant, and this was even more acute at times where welfare provisions were limited for families in crisis. Until we can provide adequate financial and social support for families dealing with complex emotional, social, and financial dimensions of family violence I fear we will continue to experience many of the same dynamics today as we did in the past.

Author: Dr Andy Kaladelfos

To cite this research brief: Andy Kaladelfos, ‘Uncovering a hidden offence: Histories of familial sexual abuse,’ The Prosecution Project, Research Brief 26, https://prosecutionproject.griffith.edu.au/histories-sexual-abuse (13 January 2017, viewed 14 January 2017).